Dear Future Teachers,

I’ve asked you to collect photos at your placements that convey some aspect(s) of your school that are not easily visible to those who have never been there or that are not easily measured by the usual assessments (either classroom or standardized) and to write about what you present in a way that will help us think about what we see going on in schools and what it means. Though standardized assessments are frequently used as a measure of the worth of a school, they represent a narrow slice of the complexity of what students and teachers do. I’ve assigned this project because I’d like us to think together about ways to represent more of what it means to be teachers and students embedded in a school community.

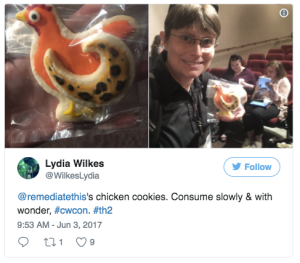

Here is my simple example. (I expect you all to outdo me!) I’m creating it in WordPress, which is sufficient to our needs, but you should feel free to use some other format if you like – Prezi, tumblr, glogster, etc. I would prefer it in digital format, but we could negotiate a paper version if you feel strongly about it.

Do I have to go to school today?

Su Lin and Healim in their national costume for Independence Day celebrations.What became most evident to me in assembling these pictures for this project was that they reflect as much about what I value as an educator (and as a parent of school-age children) as they do about the activities sponsored by the school.

Gavin and his “Big Sister” at an event that matched students from K-8 with big brothers and sisters from grades 9-12.I’m most interested in the ways that school supports interactions between people from different backgrounds and promotes ways of valuing different experiences and perspectives while pursuing shared projects. In my mind, this is not only the work of school, but the work of living, and my working definition of love.

A college volunteer reads Padma’s stories back to her during free-reading time in class.Of course, success in this endeavor is not easy to define, let alone measure. And it’s important (to me, to students, to parents, and to administrators) that we are demonstrating adequate gains in reading and writing. Literacy skills have the potential to improve quality of life not only in monetary ways, but also in emotional and psychological ways. Telling your own story in your own words (and respecting the stories of others) in a diverse society committed to accurate representation and acknowledgment of its citizens is important. Even if you feel all those pieces are not in place yet.

Healim, Sadvhi and other students taking a knitting break with the knitting club sponsor (that’s me!) on a school-sponsored hike.Building that kind of tolerance takes a lot of work. It isn’t enough to tell students that they matter or to instruct them to listen to each other. You have to do those things, and you have to model it in your own behavior. You have to spend time on developing the kinds of relationships that show students that they matter. You can invest that time in class and/or out of class, but you can’t short-cut it.

Students read their versions of “Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day.”In my classes, we discuss it in the literature we read as a means of practicing for in-person application, and we practice it in a controlled and heavily structured way in writing workshop and gallery walk activities, where students are given the chance to respond to their peers’ work and to know what it feels like to receive response to their own.

I’m sure that on those “performance” days, there were many

We made it to the top! Students leap for an action shot at the end of our hike.students who were not excited to go to school. The dread inherent in exposing your work to criticism is keenly felt in people whose whole lives revolve around their relationships with peers. They need practice to endure, and they need peers and mentors they can trust to even give the practice a chance. We have to value more than what students can do on a test to build that trust.

Students playing “spoons” at a class night dinner at my house.There’s a popular poem by Tom Wayman, which often gets pinned to teacher bulletin boards, called “Did I miss anything?” The poem suggests that when students aren’t in school, it’s not just the content of the course that they have lost, but the opportunity to engage with other people in a way that prepares them for the way life works. It’s a little heavy-handed, and not something I’ve ever put up in my classroom, but I’d like to bend its message just a bit into a shape I like better, and say:

You have to come to school today, because we will miss you (and everything you have to share with us) if you don’t.